2014 The necessity of the democratisation of the market

The Alliances to fight poverty held at Marseille a seminar on “the market, the necessity of regulation!?”. (You find the presentations by double clicking on the names in blue.)

The Alliances to fight poverty held at Marseille a seminar on “the market, the necessity of regulation!?”. (You find the presentations by double clicking on the names in blue.)

This question looks like preaching to the choirs. But, the discussion on regulation is not neutral. It depends on what you want, on the purpose of regulation. And here comes the question of who defines the purposes? Regulation or deregulation is about democracy.

The market can be seen as a social invention. It has equalised man; everyone is equal in the market. Or they should be!? The market has been a prerequisite for a democratic society. But is it still a prerequisite? Regulation or deregulation of the market is rather a question about the democratisation of the market. Can we democratise the market?

To democratise the market is to include everyone in the market. It is about inclusion, not exclusion. Can we organise the market so that is works for a more social, sustainable and democratic society.

These questions build further on the discussions of the Alliances on the necessity of the enhancement of the social and civil dialogue. These questions have been explored in the Marseille seminar. We have looked at the financial, social and housing sector where the discussion about regulation and deregulation is essential.

Exclusion has become the norm

From our start in 2010, the Alliances to fight poverty stressed the link between fighting poverty, inequality and the lack of participation. Fighting poverty cannot work isolated from other policies. Moreover, one of the huge challenges is to develop an anti-poverty policy that is linked with social, economic and cultural policies.

This challenge is enormous. But, an integral policy that embeds all policies isn’t today possible anymore. Politics has become schizophrenic since the crisis. Since then, we hear two discourses: a discourse on the adaptation of economic demands -even in countries that decided to loosen up the budgetary constraints- and at the same time a discourse on poverty. We find this doubletalk in the strategy Europe 2020 who wants to unite the economic, social and climate strategies. Impossible combinations.

Because of these impossible combinations the performances on fighting poverty are really bad : in 2012, 25% or 128 million people were threatened by risk of poverty or exclusion in Europe. The adaptation and austerity policies are paid by the poor, those who aren’t rich, by those who have an migration history, by those having a lower education, by those without a decent job, etc.

The consequence of the schizophrenic politics is the doubletalk: the discourse on poverty became a discourse of the deserving poor people. The discourse became a discourse that excludes, a discourse that separates ‘good poor’ from ‘bad poor’.

The prophets of the adaptation policies told us always that the crisis is just a temporary phenomenon and after the crisis we can return to a pre-crisis state. But what are the results of these adaptation policies?

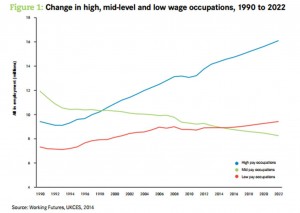

An example: a recent document from ‘Centre for cities’ in the UK (September 2014) shows the result of the adaptation policy. More than 20% workers in the UK have a weak remuneration. And the previsions aren’t good: the existent cleavage grows between the well paid jobs and the weak paid jobs. The chart shows the growing distance between the in’s and the out’s.

One of the reasons is that the reduction of unemployment in the UK is the result of an extreme flexibility. An example: workers are asked to become independent or to work only when their superior asks them to.

One of the reasons is that the reduction of unemployment in the UK is the result of an extreme flexibility. An example: workers are asked to become independent or to work only when their superior asks them to.

In Germany more than 43% of the workers have an uncommon job: part-time, one hour job, temporary job. In the eastern part of Germany more than 60% of the working population have such uncommon jobs.

Flexibility became ‘flexi-poverty’. If the ‘adaptation prophets’ can realize their goals, the future doesn’t look bright for those not having a job nowadays.

The pre-crisis-state doesn’t exist anymore. The policies of adaption have changed the course of our social model.

At the same time, huge amounts of people are looking for a job. Unemployment levels in Europe stay high. More than 25 million are at the search of a job or don’t find a job anymore. In particular in Spain and Greece the levels stay high: 25 to 28% of the persons don’t have a salary anymore. From the start of the crisis, now more than 5 years ago, these people are without hope. The maxim ‘no future’ became real and concrete for them.

We can conclude that the adaptation and austerity policies result in social disasters. Some months ago, we heard the European President saying that adaptation and austerity policies are necessary to save Europe and that they show good results. The President confirmed that Europe is back on track.

European communications were quite positive, but that was before the elections. Today the picture isn’t positive anymore. The crisis hasn’t finished: deflation, stagnation and recession are the new words. We see almost everywhere a deflation of salaries and, as a consequence, on income. Deflation of salaries, prolonged unemployment, extreme flexibility and austerity policies push people into poverty.

Investing in social policy and civil and social dialogue is necessary

The Alliances to fight poverty always insisted on the necessity of another policy. Our Memorandum inspires to develop another policy, to build a Europe that is social, democratic and sustainable.

Our seminars want to elaborate these ideas of our network. A small summary.

In Lisbon, we evaluated the consequences for social policies of the adaptation and austerity policies. The consequences are well known: these politics undermine social cohesion, they undermine the futures of the younger, they undermine one another’s health. Investment in education, social security and health are essential for the reshape of the European Union and its member states.

In Madrid, we evaluated the policies of participation. We analysed that the adaptation policies are at the same time policies that undermine social and civil dialogue. In almost all European countries social dialogue has declined.

The social dialogue is replaced by individual negotiation at enterprise level and even at individual level. Social negotiation as an instrument of solidarity between all workers is out of order. Out of order, because it is no longer convenient for the economic demands.

The civil dialogue was always threatened in a secondary role. The European initiatives of green and white papers and the Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion only mask the lack of a real civil dialogue. Investing in a social and civil dialogue is necessary for the reshape of Europe.

The regulation of the market

The seminar of the Alliances to Fight Poverty in Marseille analysed the regulation mechanisms for the economy and social sectors. Market regulation proposals tend to be inspired by privatization and deregulation practices of the financial sector. Regulation is about excluding bad practices. But we have to wonder ourselves that we speak about regulation, about the market or about bad practices. Are we speaking about what kind of market?

In his most recent works on civilization and capitalism, Fernand Braudel, historian, stresses the distinction between the market and capitalism. He defends that capitalism is not the market, but the sector of monopolies, the sector where others are excluded from this so called free and competitive market. The discussion between Picketty and Stiglitz where Stiglitz emphasises that capitalism isn’t the reason of the crisis, demonstrates that it is easy to make a confusion between capitalism and the market.

« The market is a social invention and a social advantage”. That is the thesis of the latest book of Laurence Fontaine, research director of the national centre for scientific research.

In this book Laurence Fontaine explores how the markets in Europe where a place where poor people could develop themselves. The study on the markets is also a study on how there’s always an tendency of regulating the entrance to that market. Regulation was necessary to protect those who were already present in this market or to forbid entrance to certain groups, like poor people.

In her research, Laurence Fontaine focuses on the characteristic of the market that has been rarely noticed until now. The market, that is free for all, may be a place, a space, a practice that forms an element of construction for the capabilities of persons. This is the reason that deregulation is necessary for them. Inclusion of poor people needs (sometimes) deregulation.

Today, we notice that the discussion on regulation and deregulation is not that simple. Some examples: non-employed people in the Netherlands are instructed to follow a dress code. Municipalities have the controlling task of this dress code. Here, regulations are made to exclude people.

In Flanders, people are trying to create a cooperative bank. One of the fundamental problems for the founders is the access to the bank system. This may look normal after the financial crisis but at the same time we see that regulation is also used in order to defend, to protect one’s position on the market. Regulations are used to develop hindrances.

As Immanuel Wallerstein stated, the core battle was and is the battle between the excluded and the included.

In the opening session of our Marseille seminar, Laurence Fontaine, gave us another view on the discussion of regulation and deregulation and on the position of the market within the capabilities of people.

After that, we enlarged the view on this discussion by introducing the concept of resilience. A word that found its traces in the research on metal, resilience is the characteristic of the ability of energy absorption by a body after a state of deformation. Today, it is a word that is used in different contexts: in ecology, psychology, development, sociology. In the ecological context, we speak about ecological resilience for the capacity of an ecological system, a habitat, a population or a species to rebuild its functioning or its normal development after being exposed to a severe shock.

Jean-Luc Dubois, research director of IRD, has elaborated this concept of resilience within the market context. The question is whether the formal or informal market (the discourse of Laurence Fontaine shows that the informal market is an invention of the excluded in order to ameliorate their condition by the market system) can be an element of resilience for people.

Jean-Luc Dubois has during the previous seminars insisted on the force of migrants and how we can learn of the resilience features of these migrants. The informal market is for them part of their resilience. Jean-Luc Dubois reveals also the links between resilience and the capabilities.

When we speak about 25% of the population not having a job, we can compare this situation with an important shock, like a global traumatism for society.

One could ask if people can return to a previous state when don’t have the means to do so, if they don’t see any hope for another life, when the causes of their trauma are still there. The concept of resilience opens this question: it links prevention, endurance and adaptation. How to enforce a population within a long term unemployment trend? How to protect a population against financial crises? How to come back to a previous state, so a pre-crisis state?

These questions raise another question: who will define the state of prevention, endurance and adaptation? And again, do we wish to return to a previous state? Are we not in need for new structures, new systems? And who will define which system or structure we need? The question of social and civil dialogue and thus democracy, reveals itself with the concept of resilience.

Jean de Munck, professor Sociology of Louvain-la-Neuve, invested in the question of democracy. In one of his latest books, he explored the link between the capabilities and democracy. One of the main elements of the capability of a person is having a voice. A voice to say no, yes, expressing a loyalty or a fatalism. The last one is not listed by Hirshman, but when we talk about resilience we know that lots of people only have a voice expressing fatalism. And that’s something else than expressing loyalty that can change this ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Expressing fatalism is expressing that you have a lack of resilience. The crisis and the policies of adaption and austerity have created a sphere of fatalism. Jean de Munck asked the NGO’s and the trade unions to look for new creative actions to give people again their voices.

Jean de Munck reflected on the relation between rights and the democratisation of the market. If we claim that the market is a social advantage, we need a discussion on the direction and the regulation of the market and thus its democratisation and the one of our economy. Jean de Munck reflected further on the position of the rule of law and rights in this perspective.

Jeremy Leaman (Ending a Fatal Addiction) is senior lecturer at Loughborough University and member of the Euromemogroup, The European Economists for an Alternative Economic Policy in Europe which is a network of European economists committed to promoting full employment with good work, social justice with an eradication of poverty and social exclusion, ecological sustainability, and international solidarity. He discussed the necessity of the regulation of the financial market. It is not only the question of regulation or deregulation (poor countries or under the Troika are excluded from the financial market or have to search on the informal market – like Sudan and BNP Paribas), it is also a question who decides.

Tana Lace (Presentation Marseille TL), professor at Riga University, talkes about the fall of the iron curtain and the consequences for Latvia. Deregulation was the key word. Alle social systems became under pressure. Latvia become an example for the new member states. But what were the consequences for the common people?

Patrick de Bucqois is President of CEDAG, the European Council for Non Profit Organisations, and is member of Social Platform and Social Services Europe. He talked about how social services work in and with the market. The liberalisation of the social services needs from social services a strategy to survive in this market.

Michel Debruyne (SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE CARE) is working at the study service of beweging.net, the new name of ACW, and is in that position a member of the advisory council for welfare issues for the Flemish government. He brought some guidelines, namely a framework for a all level playing field for those who wants to provide care services in the ‘care market’. This framework tends to counter the negative consequences of the marketisation without excluding the market.

After these interventions Renaat Hanssens (renaat hanssens) from ACV/CSC Belgium, Bruno Teixeira (ugt) from UGT Portugal and Robert Szewczyk (Regulate or not to regulate) from Solidarnosc Poland answered the following key questions:

1. What are the main threats in marketisation in your country? 2. What are the consequences for households and the rights of workers? 3. What are possible remedies: what kind of regulation is necessary?

The regulation of the housing market

The second part of the seminar was on the regulation of the house market.

The housing market is more than the market of buildings to live. The housing market is one of the important pillars of our welfare state. More it is the fundament of the “asset-based welfare state”. This asset-based welfare state ask people to look for their own provisions for their welfare. The state is only responsible for the activation of the people. Home-ownership is stimulated in almost every country and especially since 1980. When everyone has become a home-owner, then the state can reduce his responsibility for the social security. There is a strict correlation between the policy of home-ownership and a weak social security. Above, this policy has a negative influence to the fiscal policy and thus to a social policy.

The problem is that people who can’t afford a house, who can’t become home-owner, have a double disadvantage. This housing policy favors no other solutions like social housing and the welfare policy lacks enough means to be successful. So, you could say that housing is the wobbly pillar under the welfare state.

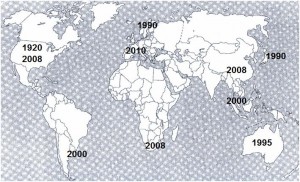

The problem with this housing policy is that it has a disastrous effect on our economies. There is a strong correlation between the housing bubbles and the economic crisis. On these map you find some of the most know. The big depression in the USA in 1930 started with a real severe real estate bubble in the 1920. In Sweden there was a strong housing bubble that has led to an economic crisis and as a consequence of the policy of restructuring a demolition of the social welfare state. The last elections in Sweden made it clear that people wanted a change of this policy of austerity that started with a housing bubble. In 1990 started a the severe housing bubble in Argentine, that ended in the bankruptcy. They are still trying to solve the consequences of the bankruptcy. We know very well the lasting economic crisis of Japan that started, yes, with a housing bubble.

The problem with this housing policy is that it has a disastrous effect on our economies. There is a strong correlation between the housing bubbles and the economic crisis. On these map you find some of the most know. The big depression in the USA in 1930 started with a real severe real estate bubble in the 1920. In Sweden there was a strong housing bubble that has led to an economic crisis and as a consequence of the policy of restructuring a demolition of the social welfare state. The last elections in Sweden made it clear that people wanted a change of this policy of austerity that started with a housing bubble. In 1990 started a the severe housing bubble in Argentine, that ended in the bankruptcy. They are still trying to solve the consequences of the bankruptcy. We know very well the lasting economic crisis of Japan that started, yes, with a housing bubble.

The housing market is more than a wobbly pillar under the welfare state, it is also the wobbly pillar under our economic system. The housing policy can creates happiness or tragedy. In our societies we see mostly tragedy. It excludes people from decent housing and creates economic problems.

Paskal de Decker, lecturer at university of Louvain and well known for his sharp conclusions, has introduced us into the housing market. After him the president of Feantsa, Mike Allen (feantsa), has discussed the problem of homelessness.

Then four country reports give us a clue how a social policy on housing is sometimes possible or mostly not possible. In France, the government has chosen the home-ownership strategy forgetting that social housing and affordable housing is needed. Patricia Bezunartea gave an overview of the housing policies in Spain: the government promises a lot to people who have lost their houses, but they do anything. Above all, there is no housing policy anymore. In Roumania almost everyone is home-owner, but has not the means to renovate the house or to pay the energy-bill. A broad strategy is not found. In Scotland they have reversed the a-social housing policy of the Thatcher period and created an anti-homelessness policy. With Scotland we ended with a policy that gives a glimpse of hope for a better housing policy.

Peter Lelie introduced the seminar with an overview of social Europe. He stressed the importance of the continuing fight against poverty, the poor results of this fight in different member states, the discussion about the indicators to monitor poverty and social exclusion and the need of global indicators for Europe.

These discussions on regulation and deregulation help us to elaborate our memorandum and to make our proposals more concrete. A further elaboration of our memorandum is now our task.

Leave a Reply